Sitting at his desk, Bernardo Soares imagined himself free forever of Rua dos Douradores, of his boss Vasques, of Moreira the book-keeper, of all the other employees, the errand boy, the post boy, even the cat. But if he left them all tomorrow and discarded the suit of clothes he wears, what else would he do? Because he would have to do something. And what suit would he wear? Because he would have to wear another suit.

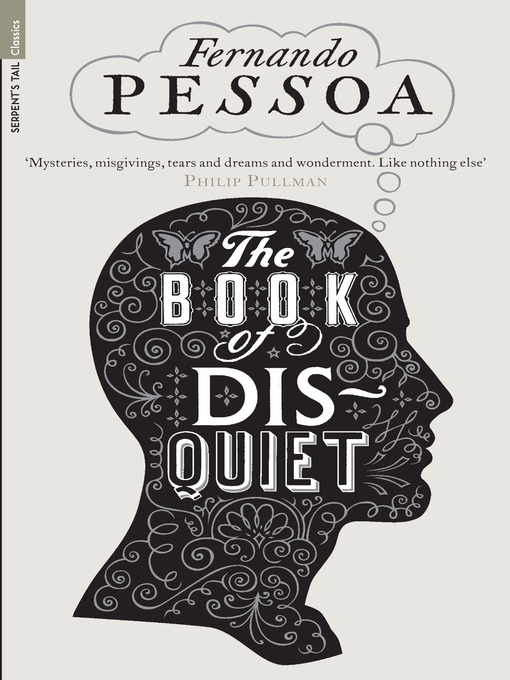

A self-deprecating reflection on the sheer distance between the loftiness of his feelings and the humdrum reality of his life, The Book of Disquiet is a classic of existentialist literature.

- Available now

- New E-book Additions

- New kids and teen additions

- Most popular

- Best of the Library Writers Project

- Black Pacific Northwest Collection

- Manga from VIZ Media

- Ukrainian e-books

- See all ebooks collections

- New Audiobook Additions

- Most popular

- Available now

- New kids and teen additions

- LGBTQ Young Adult Audiobooks

- Family-Friendly Audiobooks 🎧

- Always Available Audiobooks

- Audiobooks Read by Celebrities

- See all audiobooks collections